Saints' latest encounter with London Irish may have ended in a victory for the Franklin's Gardens outfit, but the two sides have been locking horns for over a century.

And with Northampton’s Mobbs Memorial Match fast approaching, BBC radio's GRAHAM MCKECHNIE took a fond look back at the two protagonists from the Club’s second ever clash with the Exiles…

It was a cold winter's day when Northampton Saints and London Irish met in December 1912. The skies above Franklin's Gardens were leaden grey, the wind was bitter and the sleet had turned the pitch into a muddy field. It was the second meeting of these two famous old clubs and brought together for the only time two of their most important players. Captaining Saints on that wintery afternoon was Edgar Mobbs, a man still remembered and revered at the Gardens, whose Memorial match will be played here in a few weeks. Captaining London Irish was John Dodd, largely forgotten today but who deserves to be placed in the same bracket as the man whose team he played on that Christmas afternoon. For London Irish was Dodd’s life. He had played with them ever since he came across from County Kerry and captaining them gave him his greatest pride. It mattered more to him than anything else. How do we know? Because his gravestone tells us so. Because when he was killed by a German shell in November 1918 and they laid him to rest in northern France, of all the things his grieving mother could have chosen to have on her son’s headstone, she settled on these simple, remarkable words: “Lieutenant J O’C Dodd...Late Capt London Irish Football Club.”

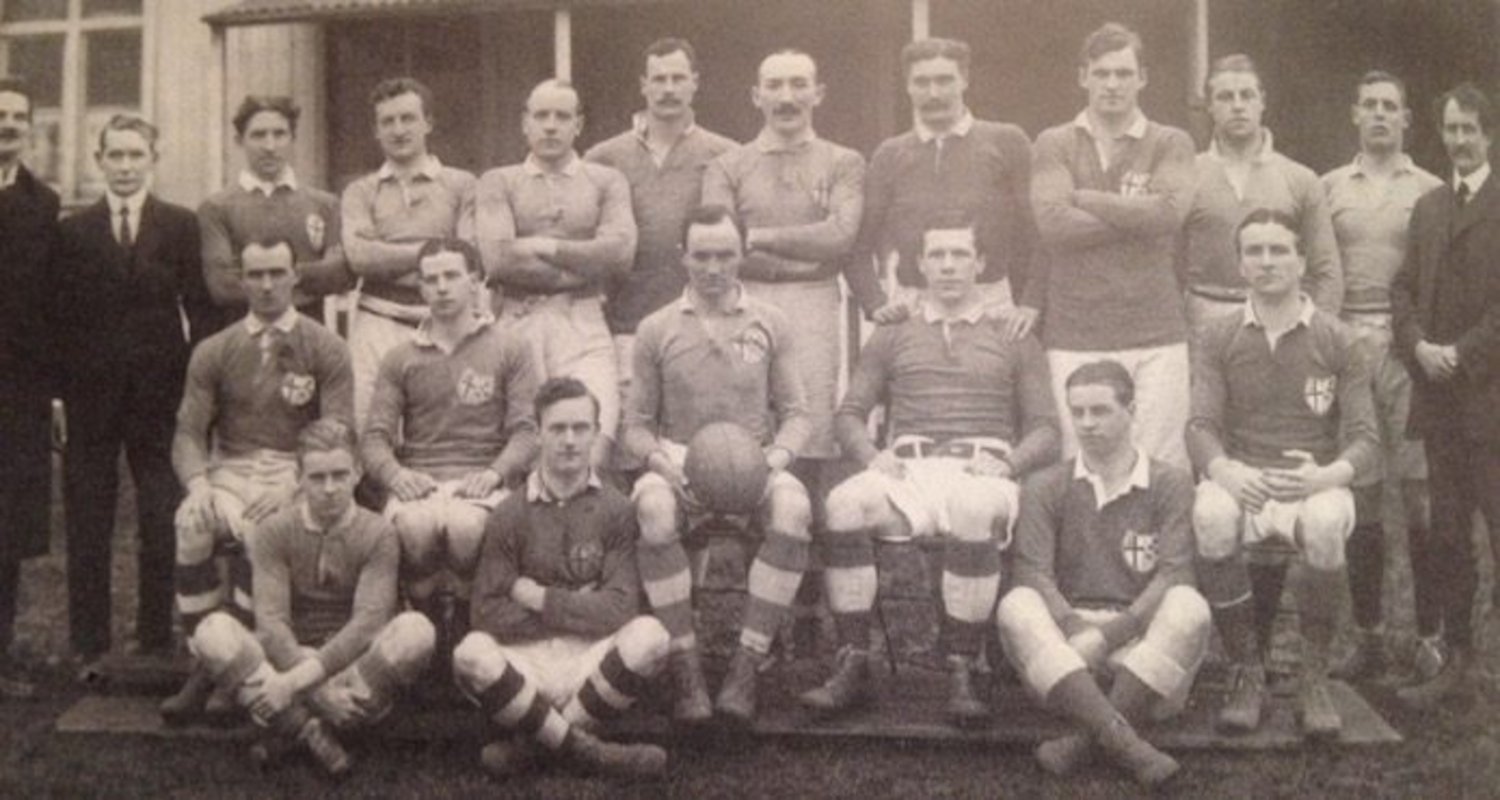

London Irish would have known all about Edgar Mobbs in 1912 and he, no doubt, would have given them his usual warm, garrulous welcome. He was Saints’ first England captain and a superstar of the sport. The match came about by chance. Irish were returning from a Christmas tour of south Wales; Saints had a free date in the calendar after Plymouth RFC disbanded to play rugby league. And so it was that Mobbs and Dodd met. The two captains who shook hands that day at Franklin’s Gardens were – and still are – the embodiment of both clubs: Mobbs the son of Northamptonshire, Dodd the Irishman in exile in London.

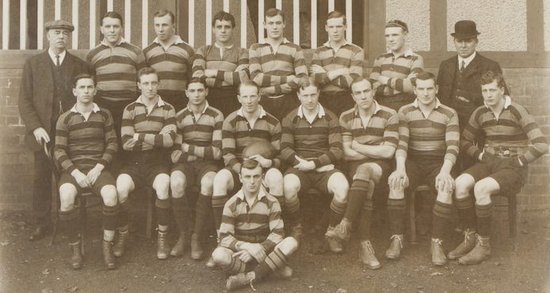

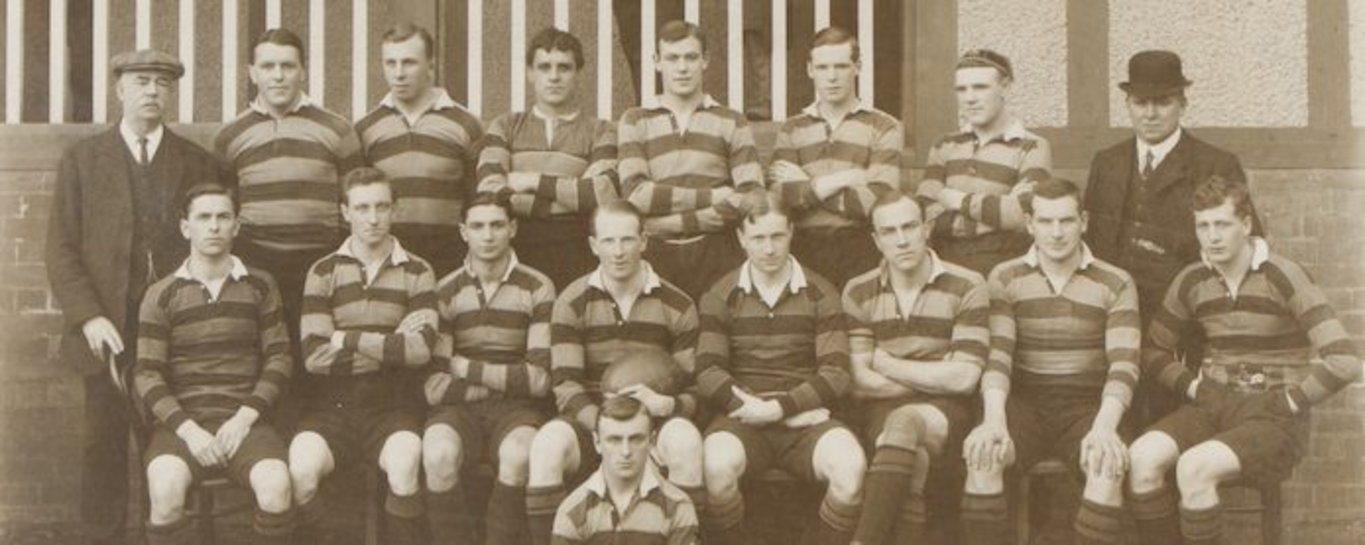

John O’Connell Dodd was a member of London Irish for almost all of his adult life. He was born in Kerry in August 1883, the son of a Killorglin doctor and one of eighteen children. He moved to London as a young man, finding work as a clerk in a legal office. Like many other young Irishmen (and two of his brothers), the newly-formed London Irish RFC became the centre of his social and sporting life. Early club records are sketchy, but Dodd – who played as a forward – appears in a second team photo as early as 1904, as a 21-year-old. Four years later he was playing regularly for the 1st XV and by 1910 he was the club captain.

For rugby players in 1914 and for both Mobbs and Dodd, it was an instinctive duty to join up and to fight and serve alongside their own. For Mobbs this meant joining the Northamptonshire Regiment; Dodd returned to Killorglin to join the 8th Battalion, the Royal Munster Fusiliers (largely drawn from Kerry men). He enlisted as a sergeant but was soon promoted, receiving his commission in June 1915. Six months later the battalion of young Irish volunteers headed to the Western Front.

It was not so straight-forward for Edgar Mobbs, but it is what made the legend. Mobbs’ story is well-known and his presence is still felt at Saints more than a hundred years later. He is an iconic figure – a tall, dashing, buccaneer of a man, loved by all who came into contact with him, flying down the wing with a powerful hand-off and a high stride which brought him 179 tries in 234 appearances. He was almost single-handedly responsible for establishing Saints as a national force in rugby in the years leading up to the First World War.

What elevates him on to a different plane is what happened during the war years. Despite his fame, when Mobbs tried to enlist he was turned down on the grounds of being too old at 32. Undeterred, he simply set about raising his own company of men. And they flocked to him – rugby players and rugby supporters – forming D Company of the 7th Northamptonshire Regiment which became forever known as the ‘Mobbs Own’. Having himself joined as a private soldier, he rose through the ranks to command the battalion as Lieutenant Colonel Mobbs, DSO. He was killed on the first day of the Battle of Passchendaele, 31 July 1917, charging a German machine-gun post which was holding up his battalion.

John Dodd’s first few months in France were spent on the monotonous, yet dangerous routine of going in and out of the line around Loos. He wrote to his brother Maurice that, “during the time I was there, we had no fighting whatsoever. Nothing on a large scale came off and we were not fortunate enough to be on the spot where any of the small fights took place”. In May 1916, while burying a fellow officer, Dodd himself was hit – wounded in the left shoulder, as he says, by “a bit of shrapnel...which left rather a big hole”. He was shipped back England, to hospital in Winchester, before going home to Ireland to recover (and to write letters to his commanding officer, begging to be allowed to return to his battalion).

An evening to celebrate the legacy of one of Northampton's finest sportsmen and leaders

Book tickets for the Mobbs Memorial Match against @armyrugbyunion for £15 adults or £5 juniors

👉https://t.co/IZEyrNLVgH pic.twitter.com/A6DyvJyAsj— Northampton Saints (@SaintsRugby) 6 February 2018

Dodd was given his wish and rejoined the fray later in 1916, but it wasn’t the Western Front for him. Instead he was posted to the 6th Battalion and headed out to Palestine to fight under Lord Allenby. He spent a year in the Middle East – at Christmas 1917 he wrote to Maurice once more, “We are having a good time here now hunting the Turks. We were indirectly concerned in the fall of Jerusalem yesterday as we were doing an attack on the flank of it”. Dodd returned to the Western Front in early 1918, initially training American soldiers who had recently joined the war, before joining the 2nd Battalion, the Royal Munster Fusiliers.

The final weeks of the First World War were as bloody as any which had preceded it. The German Army was beginning to collapse, but warfare had become much more open as the Allies were in pursuit of their prey further and further east. There was talk of an armistice, but the fighting continued. On 7 November Dodd and his men came under shell-fire. In the stark words of the battalion war diary, “At 0700 Lt Dodd commanding B Company was killed whilst transferring his men to trenches from billets owing to the increased shelling”. Four days later the war was over.

The men of the battalion were devastated to lose Dodd. He was loved by his soldiers. Letters home to the Dodd family tell of how the locals promised to tend to the grave of this “fervent Catholic and loyal Irishman” in peacetime.

Captain Livingston was with Dodd when he was killed and wrote back to his mother: “I have myself lost a brother and many good friends, but nothing has affected me so much as the death of your gallant son. He had come through so much that we never thought he would be killed. His honest, kind-hearted, unselfish character, you know better than I. On the night before his death, although himself worn out with four nights and three days of marching and fighting he insisted on doing my job because he thought I was more exhausted than he. Ireland can ill afford to lose such a man.”

There was a large crowd for the match at Franklin’s Gardens at Christmas in 1912, but they did not to see a good game. The Saints played in white that day, Irish in green, although all the players were, “very soon plastered from head to foot with mud, while rain in the second half made matters more unpleasant” (poignant words given what lay ahead for many of those playing that day). It finished 3-3; Nunan scoring for Irish, White for Saints – a man who would go to win the Military Cross in the First World War, succumbing to pneumonia on the Western Front a month before Dodd’s death. The newspaper reports do not record the post-match festivities but it is not difficult to imagine Mobbs and Dodd sharing a drink after the game. Two men with so much in common, brought together on this afternoon by the sport they loved, and again in the years ahead by the tragedy of the First World War.

London Irish could ill afford to lose John Dodd, nor Saints Edgar Mobbs. Neither deserves ever to be forgotten.

Tickets for the Mobbs Memorial Match are now on sale, with tickets priced at £15 for adults and £5 for juniors, concessions, and veterans of the British Armed Forces.

Purchase from the ticket office at Franklin’s Gardens, CLICK HERE to book online, or call the Saints Ticket Office on 01604 581000. Please note that this fixture is NOT included in the 2017/18 Season Ticket package.