With Black History Month in full swing, Club Historian Graham McKechnie has uncovered the remarkable story of Northampton Saints’ first mixed-race player, Frank Anderson.

You can listen to a documentary on Anderson’s life, presented by McKechnie and Saints skipper Lewis Ludlam, by clicking HERE.

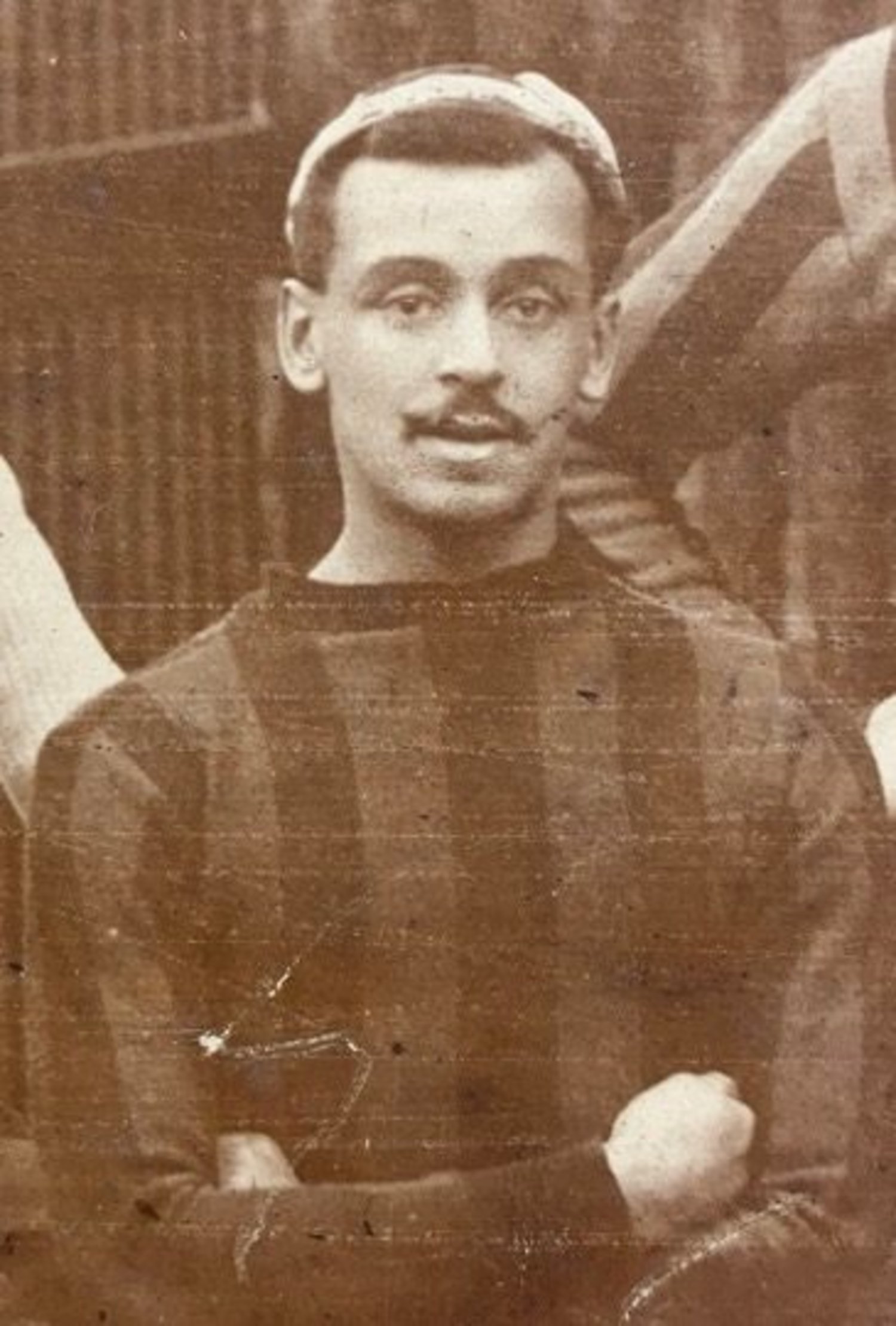

Frank Anderson is a Saints player who has been totally forgotten. With just nine first team appearances spread over a couple of seasons, you can understand why. It’s impossible to remember everyone who’s worn the jersey – there’s more than two thousand – but Frank Anderson is special.

His story is one of extraordinary triumph over adversity, of rising out of a Victorian slum to play for his hometown team, and then later to do his bit and more in the First World War. Frank is also a first; Saints’ first mixed-race player, and for that alone he should be remembered.

Frank was born in Northampton in 1878. His mother, Eliza, was from Spring Lane – at the time a rabbit-warrens of terraced houses, a typical Victorian slum which was all-too common. His father, Charles, was a man of colour from Baltimore. It states clearly on the early censuses that he was from Maryland in the USA. Quite why he chose to leave to come to live in Northampton is something we will probably never know. They lived together at Spring Lane Yard, along with Frank’s younger brother Harry. Charles was a currier’s assistant, tanning leather for Northampton’s shoe trade.

We know little about Frank’s early life in Spring Lane. We can safely assume he went to Spring Lane School, which is still there today. That’s about all that Frank would recognise of his childhood home, as modern high and low-rise buildings have now replaced the terraces.

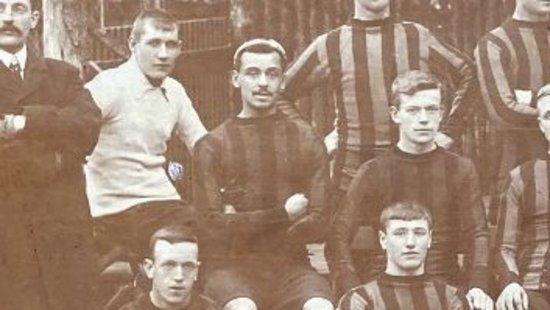

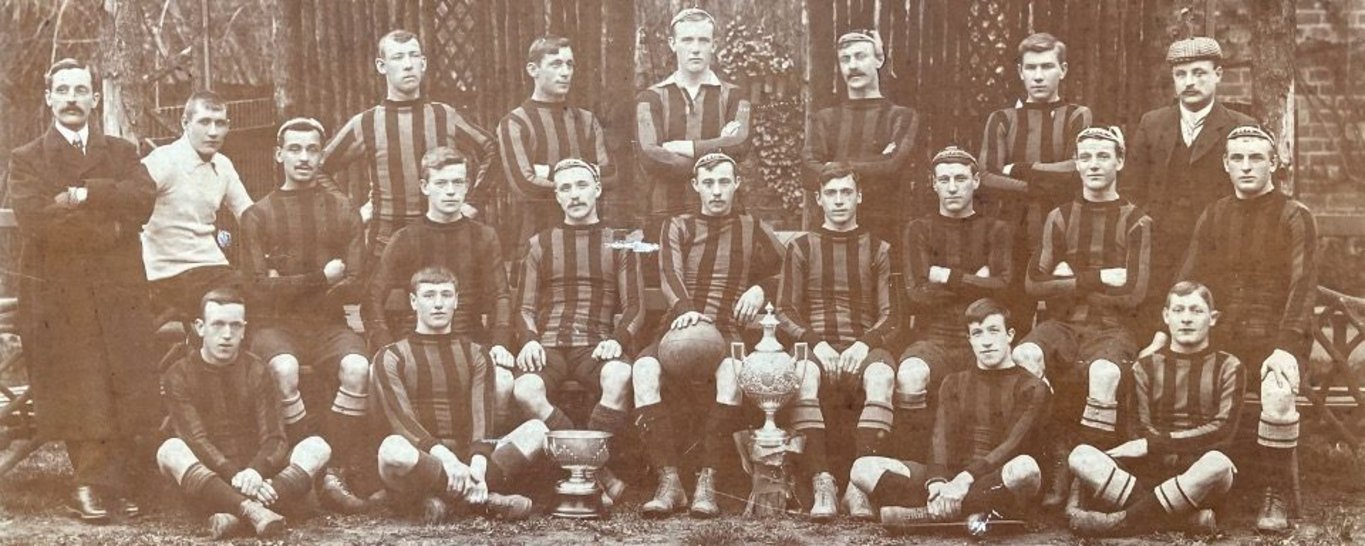

By the late 1890s, Frank was playing for Saints’ A team. Records don’t exist for A team games, but newspaper reports refer to him as making many appearances for the reserves. Despite standing at only 5’8’’ and weighing a little under ten stone, Frank played in the pack. He was clearly well-liked and respected by his team-mates, as they first made him Vice-Captain of the A team, and subsequently secretary too.

The first of Frank’s nine first team appearances for Saints came on 20 October 1900, when an injury to Harry Atterbury gave him his chance against Coventry. A run of first team games continued that autumn and into December, but with Atterbury fit again, Frank was thrust back into the reserves.

There are little glimpses into Frank’s life away from rugby we can pick up from archives and the Northampton newspapers. We know he worked in a shoe factory, like most of his Saints team-mates. He moved to Muscott Street, just round the corner from Franklin’s Gardens, at some point during the 1890s to live with his new wife, Amy, and baby daughter Ethel – and four Thorneycrofts, his wife’s father and brothers (one of whom, George, also played for Saints).

On 22 December 1900, Frank was playing for Saints’ first team against Portsmouth at Franklin’s Gardens. Word reached the players that some Northern Union agents were in the ground, looking to sign full-back Cock Leigh for one of the professional clubs. Saints’ players pursued the hated agents, apparently with the intention of throwing them into the lake. But they were given the slip, and instead the pursuit went through the pubs of Northampton. In the end, Frank and two West brothers (who also played for Saints) cornered the agents and floured them in the Ram Hotel on Sheep Street. A fight broke out between the three Saints players, the landlord of the pub and other hangers-on. Police were called and arrests were made, with everyone accusing the other of throwing punches. When the case eventually went to court, the story was so complicated the prosecution suggested all charges should be dropped. To the relief of all, the mayor who was presiding over the case agreed.

Frank’s name appears again in the papers in 1908 when he was assaulted on the train from Castle Station to Long Buckby (where he was now working, in the Cook & Co shoe factory), but apart from that and occasional mentions of him in A team matches, he fades into obscurity like most men of his class.

The First World War changes everything. Despite being 37 and relatively old, Frank volunteered to fight. He appears to have been working in a shoe factory in London at the time, with the family still back in Northampton. In January 1915, the recently-formed 17th Middlesex Battalion paraded through London. Frank joined them the next day as a private.

The 17th Middlesex was no ordinary battalion. They are known as the Footballers’ Battalion – set up in response to the criticism professional football was receiving for carrying on when most other sports stopped. They recruited professional footballers and the men who followed the game. Today, their most famous member is Walter Tull.

Frank Anderson and Walter Tull were in the British Army together. This is a quite extraordinary fact. Walter Tull, the first mixed-race footballer at Northampton Town, and Frank Anderson, the first mixed-race rugby player at Northampton Saints.

Can this be a coincidence? Two sportsmen of colour from the same town, surely at the time would have known each other. This could be why Frank chose to join the 17th Middlesex, out of all the dozens and dozens of battalions, in the British Army.

They served together from January 1915 until Tull left the battalion with shell-shock in May 1916. They were both NCOs – Frank an acting lance corporal and Walter a sergeant. There is no question that they must have known each other here.

I’ve absolutely loved working on this with @GrahamMcKechnie , It’s an incredible story and one I think you’re all going to really enjoy. https://t.co/EbD69YqRiN

— Lewis Wesley Ludlam (@LewisLudlam) October 13, 2021

Tull left before the Battle of the Somme in July 1916 (although he was to return as an officer in the 23rd battalion later in the year. Anderson remained and fought with the Footballers’ Battalion at the infamous Delville Wood on 28 July. Of all the dreadful places to be on the Somme that summer, Delville Wood was just about the worst. Thousands perished in the chaotic fighting, amongst the shattered tree stumps and barely recognisable trenches. Frank was wounded but stayed at his post. He would go over the top with the battalion at Guillemont less than a month later, and in October 1916 he was awarded the Military Medal, for ‘bravery in the field’.

Frank’s war came to an end in November 1917 when he was crushed by some timbers he was helping to move, breaking a couple of ribs. He would stay with the army until 1919, but back in England and reunited with his wife and three chidren (son Harry and daughter Doris had been added to their home in Upper Priory Street).

After the war Frank returned to life working in a shoe factory, but again he had to travel to London for work. In the summer of 1921 he contracted acute miliary tuberculosis, an illness sadly too common amongst the poor at the time. He died in the London Temperance Hospital on 4 July 1921 at the age of 42.

Frank was a poor man, and his family could not afford to bring him back to Northampton. Instead, he is buried in an unmarked communal grave in Islington and St Pancras Cemetery. Today, his grave is covered with brambles and ivy in a forgotten corner of this vast, sprawling cemetery – a sad place for anyone to be, but especially a man who had overcome so much.

It was by chance that I spotted Frank in an A team photo from 1903. Tull is rightly taught in primary schools across our county. Saints’ current Club Captain, Lewis Ludlam, and I had the privilege to attend Spring Lane Primary School’s Black History Day in October 2021.

They learnt about Tull and other figures from British black history. But they also learnt about Frank Anderson, one of their own. I can understand why he has slipped into total obscurity, but it’s our job now to make sure he’s remembered. Discover more of Northampton Saints history today.